“Tunic” is a love letter to games, nostalgia, and remembering what it was like to love the journey. (Spoilers)

By: Joshua Ceballos

“Tunic,” a Zelda-like adventure game about a little fox, was recently on sale for free in PlayStation Plus’ monthly games, giving me a chance to try it for the first time.

If you haven’t played it, I urge you to go do so right now. I’m serious. Go buy it. If you downloaded it and haven’t played it yet, boot it up as soon as you can.

No game in recent memory has so completely captured my attention in both my waking and dreaming hours. I was out at social events thinking about going home and playing Tunic. I was mulling over the next puzzle while eating meals. I was untangling the next mystery in my head when I had any free time.

I could spend paragraphs and paragraphs talking about the game’s world, its level design, or the way it leads you on a breadcrumb trail of clues until your mind eventually expands and your entire perspective on the game changes again and again.

But instead, I’d like to talk about the game’s message. At least, the message that I took away from it.

SPOILERS AHEAD.

It’s no secret that Tunic wears its classic Zelda influence on its sleeve. The player character wears a little green tunic, there’s scattered references to “The Hero,” and you find your first weapon in a dark cave near the start area.

But more than just an homage to Zelda itself, Tunic is a love letter to the era of games Zelda comes from, and the feelings they evoked in players who experienced them for the first time in a pre-internet world.

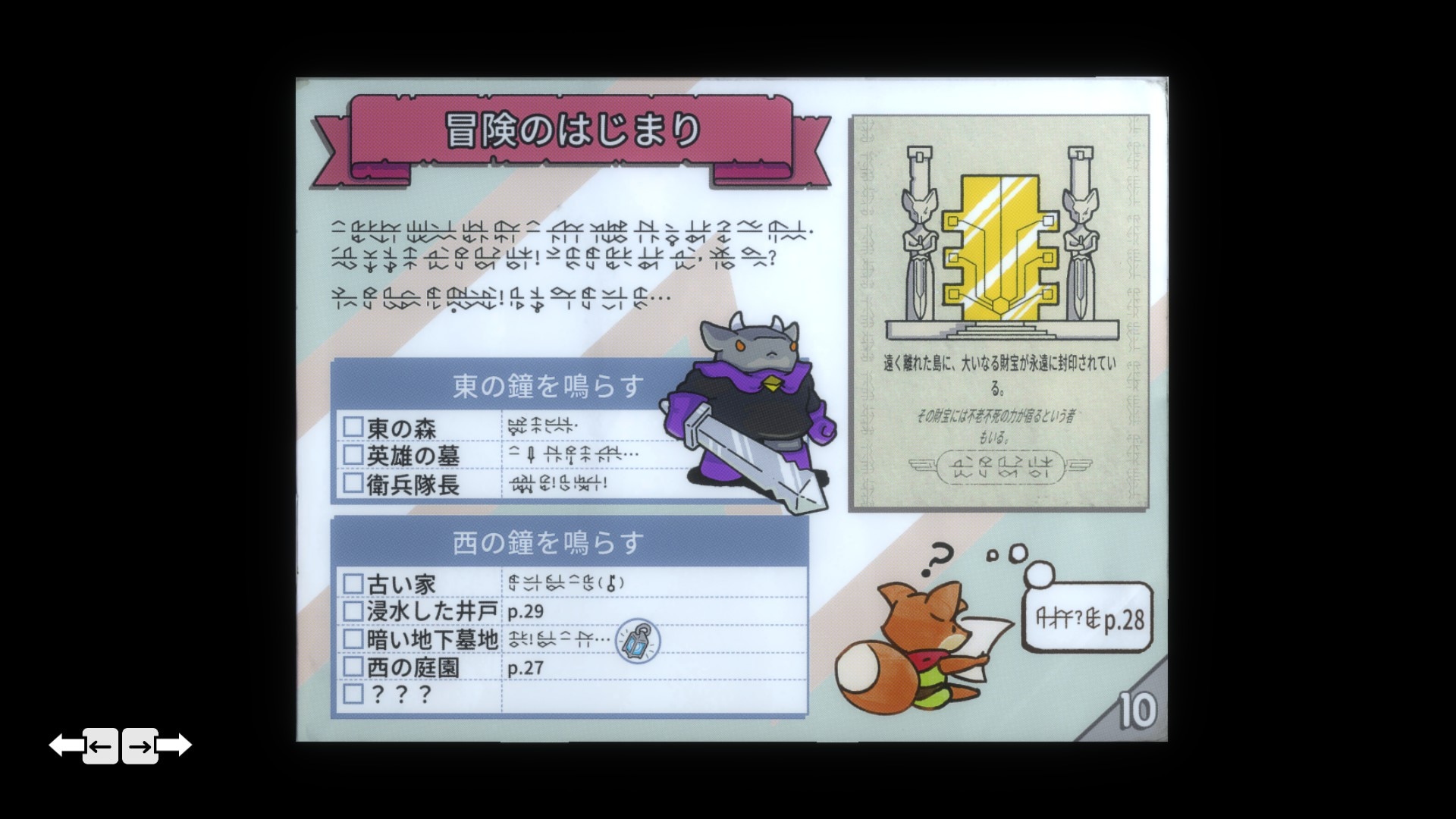

Nowhere is this more evident than in Tunic’s in-game manual and guide — a recreation of old-fashioned game guides that used to come in the box whenever you’d buy a new game. Tunic’s like the manuals of old, offers plot, lore, helpful tips, and maps of the various areas, if you can decipher the game’s unique language.

The game has two endings: Ending A, where you fight and kill the final boss, the Heir — a spectral adult fox trapped in a spiritual prison; or Ending B, where you complete the game manual and share it with the final boss. When you share your wisdom with the Heir, they drop their sword, drop to their knees, and weep. Then their spectral form dissipates and they turn into a normal adult fox, with the same clothes the hero is wearing. The player is then treated to a sweet series of shots during the credit roll where the little hero and the boss are exploring the island together and playing games side by side.

While there’s been a lot of great analysis of Tunic’s actual story and lore, and many of those interpretations are probably more textually accurate, this is mine.

When I saw this ending sequence, it felt to me like reminding my older brother about the games we used to play with each other, and the experiences we had growing up playing games. He was the Heir, and I was the small fox.

For anyone else this could be sharing an experience with your older sibling, older relative, or even your inner child sharing a memory with your adult self. To me, though, I thought of my brother.

As we get older, maybe our tastes change and we start liking more “mature” games, like Dark Souls (the Heir does fight a lot like a FromSoftware boss). Maybe life and adulthood get in the way of our memories, and we’re so focused on the slog that we get “trapped,” for the lack of a better word, in a cycle where our first instinct is toward aggression and facing a problem with a blunt approach.

In this way we forget, like the Heir, what it was like to be a kid and enjoy the journey.

Tunic, therefore, reminds us of the experience of discovery, of sharing memories with our loved ones, of rediscovering what made something fun in the first place. Playing Zelda, Jak and Daxter, or whatever with your loved one and reading the manual and finding all the little secrets together.

This game is for me and people like me, who in our most transparent moments realize that gaming has been such a huge part of our upbringing. It’s the connective tissue that strings together so many memories of happy times. Times playing alone, yes, but also times playing with friends and family and sharing stories about our latest adventures.

Throughout the years we’ve spent growing up and getting jobs and falling in love and worrying about tomorrow, there’s always been this escape, this artistic medium that transcends time to bring us closer to each other and to ourselves.

Tunic is about so much more than just the game you’re playing. When you figure out the secret of the “Holy Cross,” that this in-game esoteric relic is actually just the directional pad on your controller, you realize that this is way more meta. This is a game about games. This is a piece of art for the people who treasure gaming as more than just an occasional hobby. It’s for the kids who watched their siblings playing something and were enchanted by everything that happened on screen. For the kids who read the manuals cover to cover, who stayed up late thinking about digital worlds, only to fall asleep and dream up the solutions to puzzles they couldn’t crack in their waking hours.

I came out of Tunic not only screaming from the rooftops and texting every friend I have telling them to play this game — it also made me want to call my brother. I wanted to spend time with my loved ones and let them know how much they mean to me. That’s what this game does.

The final achievement you get when you roll credits on the “good ending” says: “Thank you for playing.”

I think that really gets to the heart of what this game is about.

It’s not only a “thank you” to Shigeru Miyamoto, or Nintendo, or Zelda, or to games; it’s a thank you to the players. To the people who have spent their lives playing games and enjoying them, and then went on to make friends who played games, and then went on to make communities online and in real life all about celebrating this beautiful medium.

“Thank you for making this artform and subculture so special. Here’s a little gift just for you,” is what I imagine Shouldice and his team are saying to us.

Tunic is so incredible, and it’s up there with “Outer Wilds” among games that I wish I could erase from my memory so I could play it for the first time again.

Thank you, Andrew Shouldice for making this game. And thank you to all the people out there who have made this hobby so so special.

Find me on X @BarrelRollBlog_

Leave a comment